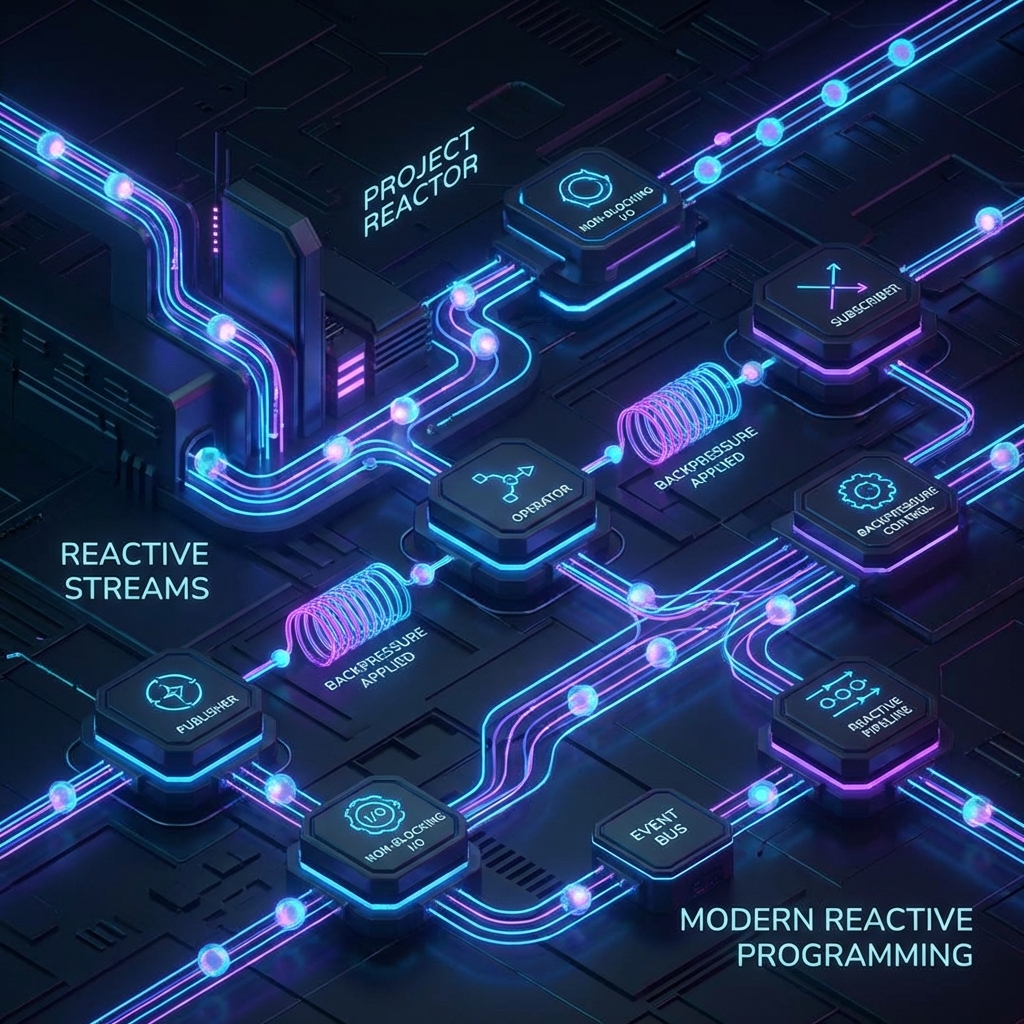

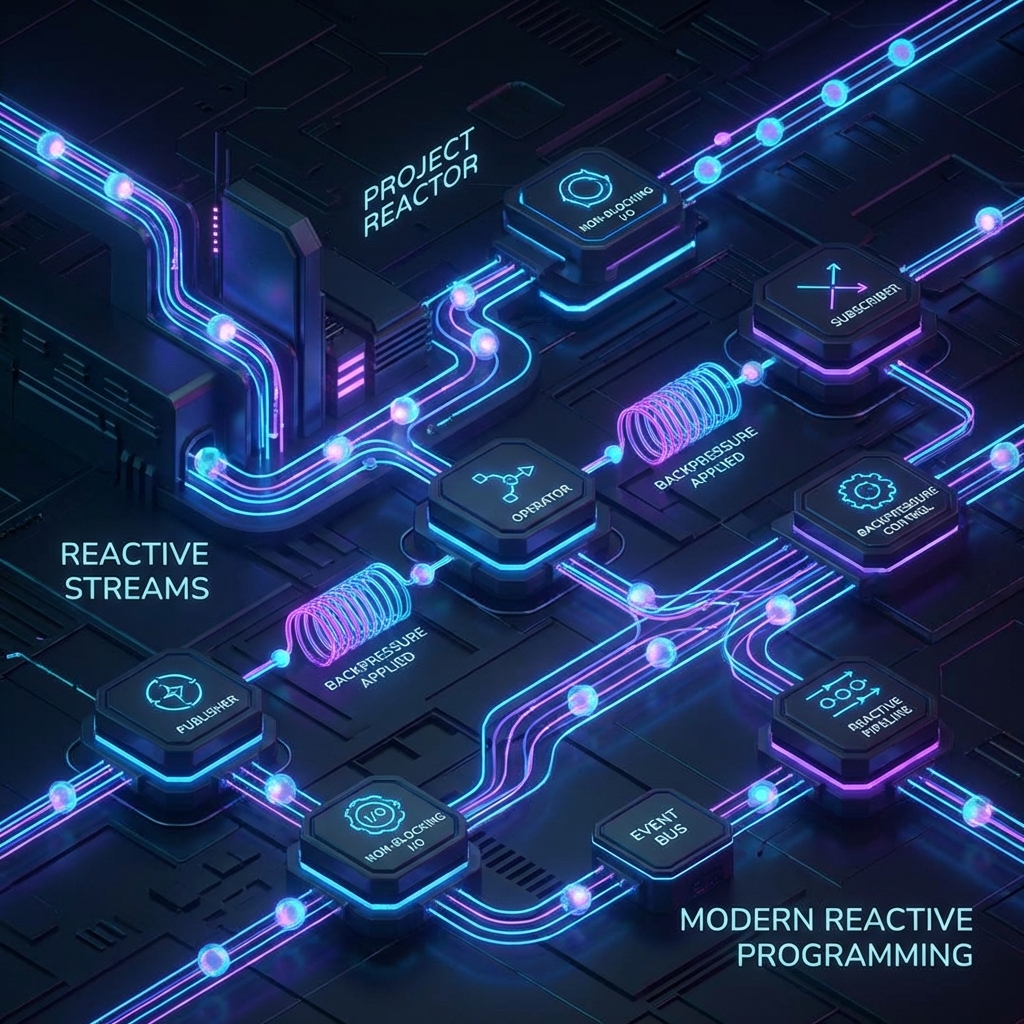

Reactive Streams: When to Use Project Reactor

Reactive: Hype vs. Reality

Reactive programming promises infinite scalability with non-blocking I/O. The reality? It’s powerful but comes with complexity costs. You need to know when to use it.

The Core Problem Reactive Solves

Traditional blocking I/O: One thread per request. Under high load, you run out of threads.

Reactive I/O: Thousands of concurrent requests with a small thread pool. Requests don’t block threads while waiting for I/O.

The Numbers

| Approach | Max Concurrent Requests | Memory Usage | | :— | :— | :— | | Blocking (Tomcat) | ~200 (thread pool limit) | High (1MB per thread) | | Reactive (Netty) | 10,000+ | Low (event loop reuses threads) |

Project Reactor Basics

@GetMapping("/users/{id}")

public Mono<User> getUser(@PathVariable String id) {

return userRepository.findById(id) // Non-blocking DB call

.flatMap(user -> enrichmentService.enrich(user)) // Non-blocking HTTP call

.timeout(Duration.ofSeconds(5));

}

Key concepts:

- Mono: 0-1 element stream

- Flux: 0-N element stream

- Operators:

map,flatMap,filter, etc.

When to Go Reactive

✅ Use Reactive When:

- High Concurrency + I/O Bound: Chat servers, real-time dashboards, streaming APIs

- Backpressure Control: Consumer can’t keep up with producer

- Event Streams: Kafka, WebSockets, SSE

❌ Avoid Reactive When:

- CPU-Bound Work: Image processing, ML inference, encryption

- Simple CRUD: Traditional REST APIs with low traffic

- Team Unfamiliar: Reactive debugging is hard

Backpressure: The Killer Feature

Reactive Streams handle slow consumers gracefully.

Flux.range(1, 1000)

.publishOn(Schedulers.parallel(), 10) // Buffer size: 10

.doOnNext(i -> slowProcess(i))

.subscribe();

If slowProcess can’t keep up, Reactor buffers and applies pressure upstream to slow down the producer.

Common Pitfalls

1. Blocking in Reactive Code

// ❌ BAD: Blocks the event loop

Mono.fromCallable(() -> blockingDatabaseCall())

.subscribe();

// ✅ GOOD: Offload blocking work

Mono.fromCallable(() -> blockingDatabaseCall())

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.boundedElastic())

.subscribe();

2. Not Handling Errors

// ❌ BAD: Errors kill the stream

flux.map(this::riskyOperation);

// ✅ GOOD: Recover gracefully

flux.map(this::riskyOperation)

.onErrorResume(e -> Mono.just(fallbackValue));

3. Mixing Blocking and Reactive

Don’t mix Spring MVC (@RestController) with reactive data access. Pick one paradigm.

Testing Reactive Code

@Test

void testReactiveEndpoint() {

StepVerifier.create(service.getUser("123"))

.expectNextMatches(user -> user.getName().equals("John"))

.verifyComplete();

}

StepVerifier lets you test asynchronous streams synchronously.

The Verdict

| Use Case | Blocking | Reactive |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional REST API | ✅ Simpler | ❌ Overkill |

| Real-time chat | ❌ Doesn’t scale | ✅ Perfect fit |

| Batch processing | ✅ Easier to reason about | ⚠️ Depends on volume |

TL;DR: Reactive is powerful for I/O-heavy, high-concurrency scenarios. For everything else, blocking code is simpler and fast enough.

Want more performance patterns? Check out Caching Strategies or Java 21 Performance Tricks.